Meet the Makers - Nigel Forster (NK Forster)

Mar 15, 2015 11:12:48 GMT

Wild Violet, ocarolan, and 7 more like this

Post by Martin on Mar 15, 2015 11:12:48 GMT

Acoustic Soundboard 'Meet the Maker' Interview

Nigel Forster

Interview by Martin Robertson

www.nkforsterguitars.com

Nigel Forster

Interview by Martin Robertson

www.nkforsterguitars.com

After a long break in this series, we're back with a bang and a fascinating interview with another UK guitar maker, Nigel Forster. Building since the 80's, and a long tenure with legendary luthier Stefan Sobell on his CV, Nigel opened up to some serious questioning from Acoustic Soundboard!

Martin: When did you start becoming interested in acoustic guitars, and then what made you decide to start making them?

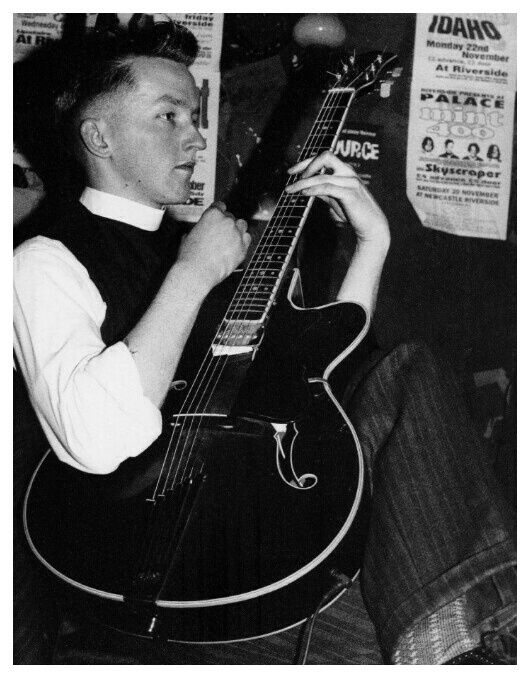

Nigel: My grandad, Charlie Ferguson played guitar in dance bands around Northumberland. So from an early age guitars were familiar to me. I had a few guitar lessons at school when I was 9 but not for long. The bug didn't bite until I was around 12 or so when I saw Will Sergeant playing his Vox teardrop on telly with Echo and the Bunnymen. Next came Johnny Marr of The Smiths playing a Gretsch, and that was it, I went off to see me grandad to ask for lessons.

So every Sunday afternoon at 3pm I'd go 'round to see him after he'd been to the pub.

Charlie had fantastic style and tone, even years later, in his 80s when his memory started to go, and he couldn't remember the chords, his rhythm and his tone were incredible.

The closest thing to Charlie's style you might know is Peerie Willie Johnson of Shetland. Look him up on YouTube, and whilst you're at it, check out Eldon Shamblin who played for Bob Wills, he's similar too. Charlie played what he called “Dance band style.” Truly musical guitar playing.

There were only a few guitar making books around then (this is the early 80s) but Charlie had some in the book case along with old copies of "Guitar" magazine. After my lesson I'd sit and read them, and making took my interest.

Back at school I started messing around trying to fix broken guitars, but the key point I guess was early on in sixth form when my class tutor, Mr Ostler asked me one morning what I'd like to do when I left school.

"Make guitars" I said.

A feller called Stefan Sobell had been in touch with my school to ask for an apprentice some time before so Mr Ostler arranged an interview. The interview must have gone well as Stefan offered me a week long "work experience." It must have gone well too as he offered me a job on the YTS scheme. Now I hadn't heard of Stefan, in the 80s, outside the folk music world he wasn't really known. The market for posh guitars was nothing like it is today. But he was the "local" guitar maker, out in the hills about 5 miles from Hexham, so that was a nice bit of luck.

Martin: So you wanted to build guitars from quite a young age, and had the opportunity to apprentice to Stefan Sobell – what was that like?

Nigel: I started my apprenticeship January 1988, I was 17. How was the work? Difficult! To go from school to the workplace is a big step. But I'd done very little woodwork so that was hard.

Some things came easier than others: I had a good feeling for timber right from the start, I was quite pragmatic and developed a good working understanding of the architecture and design of instruments over time, but handwork took the most time. I wasn't a "natural" by any means. But I was a hard working bright lad, so in time, things fell into place.

Martin: When did you build your very first guitar, and what was it like?

Nigel: It was made during the second of those first two years working for Stefan. It was a mahogany/European spruce Model O or is it a Model 1? I forget. It's not a bad guitar. I went round to see it the other day to take pictures for this article and it's ok sounding. Better than I expected.

Basically it's a typical late 80s Sobell, but in Brazilian mahogany. Stefan had been making instruments for 15 years or so by then but guitars for only a few, and looking back it's fair to say that around this time some Sobell guitars were too stiff for their own good. This one is a bit stiff, luckily the soundboard itself was rather flexible as its totally over braced. But, at the time it seemed great. And it looked nice. I gave it to my grandad Charlie as a gift, a “thankyou” for teaching me. When he died, I was given it back. One of my old pals has it now.

Martin: After you stopped working for Stefan in 2003, you began your own business – what was it like starting out on your own, and what did it involve?

Nigel: Stefan gave me the push at the end of 2003, we’d had our fill of each other by then! Mind, that worked out well for both of us. In hindsight, it should've happened sooner. I'd learned as much there as I was going to, and Stefan needed someone working for him without so many ideas of their own. We’re very different people but in some ways we are similar, similar in ways which just caused too much friction.

But as part of my “golden boot” (we'd formed a partnership of sorts some months earlier) I got some timber. I put the timber in the cupboard and looked for a job...

For much of 2004 I worked in a joiners shop in Wallsend as a bench hand joiner making doors, windows, stairs and such. It was heavy, hard work but a right laugh.

After 6 months there I fancied lighter work and went to a furniture company in Gateshead. There were some really skilled lads there some of whom were shipyard trained. So, I learned more still, but three months of that was enough.

Time to make guitars again.

A good friend offered me a loan to buy tools and I decided to get cracking on a pair of guitars. The first two were my old Model B. One rosewood, one sycamore.

Whilst my life has been rather unconventional by the standards of many, I've always been quite conservative financially - I'm terrified of debt and wary of contracts, so for the first few years I worked in the spare bedroom of my council flat! It would have been wise to get a workshop sooner than I did as working from home is bad for productivity, but still I managed 15-17 guitars a year working in that tiny room.

Now I have little experience of guitar repair, and little interest too, so from the start I set out as a maker, not a repairer who occasionally makes. This simply isn't an option for most starting out but because of my background, I could “hit the ground running”. It was like being a mechanic who'd worked for Rolls Royce - you'd have "ex Rolls Royce” on the side of the van wouldn't you? Having the background I did offered me an advantage - people already knew what standard to expect, that I wasn't a beginner.

So, I let folk know I was in business and things went well.

Martin: What is the basic philosophy behind the typical NK Forster guitar? Do you set out to achieve a certain sound and feel, and how would you describe it?

Nigel: Trying to describe sound is difficult isn't it? Most luthiers use the same sort of terms to describe our work yet it can differ greatly. Best thing to do is try one and see how it makes you feel. Next best is listen to one and do the same thing. Sound samples can help too.

Philosophy? Experiment. Question. Investigate. Challenge. Be prepared to change.

As for what I make: I make the work that interest me, that produces the sound that interests me. That's what people pay Sobell for. My business is similar in that respect. It's interesting working with customers and it's nice they trust me to do the best work I can that will suit them. They come to me ’cos they already like the sound my work makes and they know they're dealing with someone who has a fair bit of experience who is still trying to make better and better work.

In the book I came up with a line about “wanting to release the sound from these materials rather like how a sculptor seeks to liberate the statue from a block of stone” or something like that, but this year, with the structural changes I've made I feel that's closer than ever. Doing that involves letting go of ideas that have been holding the work back, ideas that I learned years ago but still hadn't challenged - ways of building and thinking which impart their own pleasant sound on the materials which might not be inherently bad, but are still a limitation on the end result.

Bracing is one of these areas. I've tinkered for years with variations on the bracing patterns I learned under Stefan, making changes here and there, but this year I've thrown that way of bracing out the window and started from scratch. The results are great, maybe, finally, it's the sound that has been waiting in those materials all along, but couldn't be released in the past because I was still “clinging” to familiar methods that produced familiar results.

Martin: Your guitars and other instruments have a very distinctive style and look – is this something you had a very clear vision of or did the style evolve over time?

Nigel: Oh, it's an ongoing and pragmatic thing. When I began, my guitars looked very "Sobell.” Which is no great surprise. I had my own shapes, different purflings and bindings too, but without question, for those early guitars of mine, the Sobell family resemblance was very strong. It wasn't intentional, that's how I made guitars, but it worked well for me as at the start many customers would come to me because they didn't want to wait in Stefan's list or pay his prices both of which more or less doubled in 2004.

But over time both the sound and the appearance of my work changed. The big change visually though happened around 2008 because of the credit crunch! That's when I made the decision to make a stripped down model, and when I did, I really liked it. It was a pragmatic decision.

With my work, form follows function. So if you're wondering “why does he do that?” the answer will be “because it makes for a more efficient structure.” But functional doesn't have to be ugly. Beauty is a function too. Why do I make those humpy top guitars? Because you can make a lighter soundboard that is just as strong as a regular one. Why the new square bridge? Because it's foot print is smaller than a regular one but it's stronger, lighter and allows greater soundboard movement.

Martin: What about your customers? How do they select you, how you filter them, how clear are their requirements? How does the commissioning process typically proceed?

Nigel: Usually at least a third of my work every year is repeat customers, folk who've either bought from me or bought a used instrument of mine. But new customers will have seen a friend's instrument and liked it, seen it at gigs: word of mouth. Then there is the web: some will be searching for a Sobell guitar and hear about me, others are messing around on YouTube or SoundCloud and find me, some find the book first, then get in touch.

It's odd, 80-90% of my customers are outside the UK, and many of the first time buyers have never even seen one "in the flesh" so I guess it's all the information out there - video, sound samples, reputation, recommendation and writing that helps folks decide. Who knows?

www.youtube.com/user/Nkforster

Filtering is easy - the lack of "bling" in the work gets the numbers down significantly!

People get in touch, and I send them a price list, if what I do fits in with their budget, we start talking about what they might like. Some folk are very specific, some not. Either is fine. The only difficulty comes when what someone wants is either in defiance of the laws of physics or wants something that isn't what I do. But that's not so hard to resolve, I explain things as well as I can, and they decide for themselves.

One of the nice things about having done all this a long time is folk tend to trust me to make many decisions on their behalf. I listen to what they're after, and see which combination of ideas would work best for them. Sometimes we have to iron out the differences between what they think they want and what would suit them best, but folk let me get on with it, which is nice. But that's usually because what we like is pretty much in alignment.

That's the key - find a maker whose preferences are in alignment with your own, aesthetically and sonically. You wouldn't ask Bentley to make you a Morgan would you? Or vice versa. That's probably why I don't get many emails asking for wedges, bevels, fan frets, inlays etc... Usually players come to me because their number one priority is sound and that suits me fine.

Martin: How long does an average build take, and how would you briefly describe the process?

Nigel: I've no idea how long it takes, but too long probably. Most of the time seems to be spent with the Hoover in me hand too, not a chisel!

As for the process...You know, one of the reasons I broadened the subjects I cover in my blog is that the process of guitar making is pretty much the same for every guitar, regardless of who the maker is. But there are quite a few aspects of my work that aren't “standard” - the bracing, the internal construction - and that I've no wish to share.

I do experiment with technique though as some ways of working are more conducive to a better instrument: these days it's a mix of hi-tech and low-tech. Hi-tech by having fretboard radius and bridges machined by cnc (I'm done with breathing in all that foul dust.) Low-tech like planing soundboards: when you plane spruce it comes out stiffer than if you thickness sand it to the same dimension. It's a matter about using the appropriate methods for each process to get the best result.

Martin: You now make a diverse range of acoustic instruments. Other than the standard steel string acoustic guitar, what other instruments do you make?

Nigel: I always have made instruments for the folk world: bouzouki, cittern, mandolin, and guitar bouzouki. I have also made quite a few Jazz archtops. That's about it. Each year seems to take a different flavour. There have been quite a few archtops the last two or three years. This year not so many, but a lot of guitar bouzoukis and mandolins. It's nice to switch about.

I made myself an electric a few years ago, but I made the mistake of posting it on Faceache, and an old customer in Hong Kong bought it the next day! Recently a good friend and customers in the USA asked for a two pickup version, so I'll be making another one of those some time this year. I call it "The Odd Ball junior." But no, it's not going to be part of the range. It's just a bit of fun. Nice guitar mind.

Martin: What are your favourite instruments to make?

Nigel: New models! Guitar bouzoukis are fascinating to make, as it's a design with only a short history - the players are not stuck with the notion that they should look or sound a certain way and that allows for much experimentation.

Mind I do wish more folk would order the Model D, it's a fantastic guitar, nothing like a typical dreadnought.

Martin: Are there any particular materials/woods you prefer working with? How do you select them, and how do they contribute to the sound you aim to produce?

Nigel: This was much easier to answer a couple of years back and my answer would have been pretty traditional, but this year there has been a shift in my thinking.

I was taught that certain woods have certain sonic qualities, and this pretty much coincides with how most makers and players think. Thinking like this provides a useful framework for people but it's also a limitation - it's not very accurate. I'm trying to forget about what a timber is and just think about mass and stiffness. Doing so may seem like an unimportant change, but it's made a difference to how I've approached work this year.

But still, I have to work with customers, and most think in terms of “Indian sounding like this, and Brazilian sounding like that.” But that's a vocabulary I understand well enough, it's just I don't find it as convincing as I did.

This all ties in with your earlier question about philosophy: Like most humans I might make an observation, which leads to a view or preference. Then I'll act in accordance with that view or preference. Now at this stage many of us switch off and our thinking gets stuck. We start piling on more views and opinions based on the original one. But what if the foundations are flimsy? So to avoid this it's important to periodically challenge your views, to ask how I came to a decision.

E.g.: I avoided bolt on necks for years because I thought I didn't like the sound of bolt on necks. Then I considered the possibility that what I didn't like was the guitars that certain necks were bolted onto! It's a subtle but different perspective that allows you to experiment. The old view didn't.

Playing and listening to a Howe Orme (where the neck is held on with a tiny dowel, a thin hinge and a pair if tiny screws) tells you in no uncertain terms that any views you may hold about the importance of a solid or glued neck joint, or the connection between the fretboard and the upper bout are probably nonsense.

Being prepared to change your mind and to let go of views and opinions when faced with new evidence is important if you care about your work's progression.

How you think about the work matters. We’re all guilty of inaccurate thought from time to time but I'm getting better at spotting the patterns of thought that hold back the work. You have to listen for silly and inaccurate thoughts or catchphrases like “transference of tone.” When you examine a statement like that you realise it means nothing, but if you think instead about the ways one physical body can or cannot set another body in motion, then you can make progress.

Another example: I was convinced for many years that I liked “the sound" of ebony bridges. Then I played my 1890s Howe Orme which has a fruit wood bridge. And it's the best guitar I've ever played. That set off a lot of questions in my mind about the bridge's role. Like many I'd fallen into the trap of thinking “the bridge is the most important brace” on the soundboard because I'd read it in a Lutherie magazine. You read a statement like that in print, nod in agreement, then all of a sudden a fixed view is formed, a view which can limit your work.

Just because you come across a view that is in agreement with what you already think doesn't mean it's the truth! Is it the most important brace? What it tends to be is the heaviest brace. If it isn't the most important brace, what is? Once again, the Howe Orme provided the answer and more questions: Perhaps the soundboard itself is the most important brace? So is the bridge even the heaviest brace? Well, if the soundboard is a brace, it is the heaviest brace too... Once again, your thinking has shifted and the work can progress. That's the main reason you won't see a fancy sculpted bridge or pinless bridge on my work. All you're doing is adding mass. Right where you need it least.

I realised some time ago that playing around with materials is a crude way to manipulate the result compared to colouring sound through soundboard design. In the past I've offered two soundboard options: standard or cylinder. Now with the new budget model there are three: standard, cylinder and flat.

The standard model is basically my version of the Sobell design I spent so many years doing. There is a line I read on the web: “NOTHING sounds like a Sobell...” well, it's a good strap line and it might be how they feel, that's fine, but that's not really the case is it? Play an early Forster, they sounds EXACTLY like a Sobell. And I've played a lot of both. Of course they do! It's not magic, it's woodwork. Despite all the structural changes I made at the time that I thought would make all the difference, listening back to my earlier "solo" work, they sound like what I'd been making for Stefan. Mind, that's not to be sniffed at, it's a sound many makers have been trying (and failing) to work out how to achieve, however it's not a sound I'm that interested in much any more. And when given the choice few of my customers order that standard design from me. That design makes a great guitar for sure, and it's a design to possibly revisit in the future but I'm more interested in the cylinder top and my new flat design these days. I can get more from them.

These two other designs - the cylinder top and flat top are a combination of several ideas: what I learned as an apprentice, my old Howe Orme, but also other influences, mainly from the Classical guitar world where I think most of the interesting sound related design work is going on.

Now I could blather on about the different tonal qualities but you'd be better off listening to the sound samples and forming your own opinions.

Model C cylinder top

https%253A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/190304600

Model S “standard” top

https%253A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/186386996

Howe Orme replica

https%253A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/179288285

Flat top “Session King”

https%253A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/195234620

Martin: You began playing guitar at 13? Do you still play, and if so what guitar and style do you use? Do you think being a player helps a builder?

Nigel: For years I was guitar daft. In my 20s I played in a band. We played a mix of 40s swing, 50s R&B and funnily enough, 60s Jamaican Ska. It was a lot of fun and we gigged quite a bit. I played a Hofner archtop at first but later built myself a non cutaway single pickup shallow body archtop, a bit like a Gibson ES150 but with a P90.

These days I only really play when I'm testing the guitars out. Every now and again I have a noodle on the Howe Orme. But I've been playing a big old chunk off my life now so it's not something I have to think about or struggle with. Playing is pretty well ingrained in me.

So whilst my repertoire is pretty limited, I have a decent right hand technique and can get a good sound from almost any guitar.

When assessing a guitar I don't have a hyper critical, analytical sense like Ian Stephenson, but I am very aware of the feeling that sound inspires in me. About how playing it feels. That's what I'm interested in. The feeling inspired by sound. Same goes for the music I like.

Guitars? I didn't have one for years - but I bought an 1890s Howe Orme a couple of years back. It's magnificent! Not everyone's cup of tea, but it is mine. It's the best sounding guitar I've ever played. And I've played a lot of posh guitars in my time. A fantastic design too, so logical and pragmatic. Rare as hens teeth, I bought this one after 15 years of searching.

As for whether it matters as a maker if you can play? No I don't think it does. It's woodwork, not magic. Actually, not playing well can be very good for business, ask Collings! What about Leo Fender for that matter? Not being a player means you constantly need feedback from others so from a marketing point of view, over time potential customers can feel they've designed the guitars themselves, so are more likely to buy. Clever that...

As it is, I can play well enough to know the direction I want the work to go without having to ask so many opinions. But it's always interesting to hear what musicians have to say though if you're too reactive to comments you end up spending your life trying to please others and incorporating every silly gimmick that comes along. That's not a very restful state of mind. You can also end up making the same guitar as everyone else.

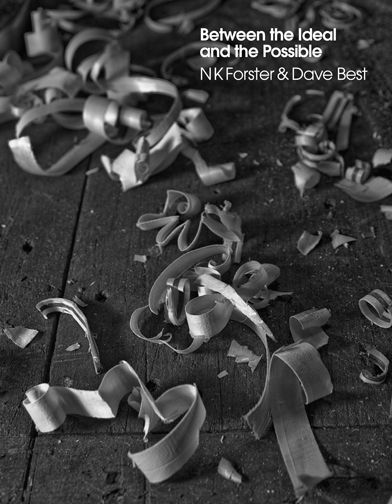

Martin: You have written and published a book (Between the Ideal and the Possible) about the guitar building process. What was your motivation for taking this on, and what have you learned as a result?

Nigel: Well, I was getting a lot of the same questions from people about various aspects of lutherie, and rather than go through stuff over and over I began putting together some essays to cover the points I felt needed to be made. Before long it was clear there was a book in this. I just needed some nice pictures to go in it. Dave Best did a fantastic job.

It's worked out well, and has provided a nice little supplementary income which was another reason for writing it. As a maker, all my eggs were in the one basket, so writing (as well as being enjoyable) has given me something to do when I've spent the winters travelling around Asia.

I learned a lot about what not to do from producing that book, but that's inevitable. I've written a revised digital edition of “Between the Ideal and the Possible” and a “How to Make a Cylinder Top Guitar” ebook and a workshop manual for luthiers but the new VAT laws for digital products have scuppered plans to release them for now. It's a shame, but there isn't much I can do about it. We shall see...a feller sent me a link to a company who can deal with all the VAT stuff the other day, I'll have to investigate a bit more.

Martin: Finally, are there any new ideas or builds in the pipeline? What's coming up next for NK Forster guitars?

Nigel: YES! My new budget model “The Session King.”

It's always interesting how ideas come to the surface. Often it's the combination of several things that produce a new design:

Last year I went to see the degree show for the Folk Music course at the Sage, Gateshead. There were some great musicians, nearly all had nice guitars, but none were made by me. Mmm....yep, it was time to look again at making a more affordable instrument.

Then I asked them “apart from gigs, what do students use their guitars for?" The answer was....

Sessions.

Could I make the perfect “session guitar”? What is the ideal session guitar?

I asked about, "What do people want from a session guitar?" The answers were pretty clear:

Loud

Robust

Not too "precious"

So this had to be a new design, not just quicker to make, but loud, robust, not too precious and affordable.

Not too precious?

That's when I had the idea of using a "relic" finish. This has been popular in the electric guitar world for years - buying a "pre worn" guitar, that already has a warm patina and worn edges. This would be a guitar that you wouldn't be frightened to take to the pub, a guitar you wouldn't worry about marking because it was already marked! As one of my pals says about old looking guitars "It looks like the tunes are already in there waiting to come out!"

But how would it sound? That's when a conversation with my old boss came to mind. We were sitting chatting during tea break, sometime in the late 90s.

"What would a guitar be like with a completely flat top?"

We thought it would sound great but at the time we just didn't know how to make a totally flat top guitar that wouldn't distort and require a neck reset. How could you do it without over bracing?

At that time, I didn't know enough to answer that question, but I do now. It's just that I understand how guitars work a lot better than we did then, I understand what is important, and what isn't. It's easy to see now how over engineered guitars are in some areas and under engineered they are in others.

It was just a case of building in line with how guitars actually should work, not with how they've been made in the past. But by making the top totally flat, the guitar becomes much quicker to produce. So it's cheaper. Compound curves makes things tricky, believe me. Yet despite the different design, it still sounds like one of mine. Only with more bass and louder!

So that's it - I made a prototype with some odd bits of mahogany I had lying around. The guitar is magnificent - super loud, robust and after a spell in the "time machine" not too precious.

So, the next thing was to try it out in a session or two. The first one was fun. Ian was playing against quite a few pipes, an accordion and several fiddles. Noisy instruments. I realised after a while that in order for the person next to me to hear me I had to shout when Ian played! Ian was grinning all night.

Next session was in Newcastle. There were a few guitar players, all with nice guitars, mainly by "small" makers like me, which is great to see. It looked like there was some really stiff competition in the room. I went to the back of the room to compare. The Session King wiped the floor with 'em, no problem! It's a winner.

In the Bluegrass world they talk about "banjo killers" that's the idea: to make a guitar that is loud enough so you don't have to "over play" and loose your tone.

I plan to build an initial batch of ten and see how they go. Those on the mailing list got to hear first. Now readers on this forum know too, so the cat is officially out the bag.

I’ll have to limit the number of these I make each year because if I'm not careful I'll end up making little else. That wouldn't be the end of the world but there is other stuff I like to make. I will try and keep the price down as long as I can, but if the demand gets too much, the price is the only tool I have to keep the waiting list reasonable. The Model S started as a £2000 guitar, they're a lot more now, but that's the nature of supply and demand.

So the future looks interesting. I've done a lot of traveling the last few years but that won't be the case for a while yet. Too many folk waiting.

Initially I intended to make this a "one size fits all." Like Henry Ford: "you can have any colour you like as long as it's black." But not surprisingly people want different things. Some want a spruce soundboard. Fine, that's a possible upgrade. Now for others, they're not very comfy with the "relic" finish. That's ok, you can upgrade that too. But for now I will limit this model to two body shapes: the Model C and the guitar bouzouki body which is a bit like a short Model S, and makes a great guitar shape. In the future I may roll it out to my other shapes.

But it's very exciting, it's nice to make a guitar that you know is going to get played, and that's not always the case.

We shall see how it goes.

Nigel

www.nkforsterguitars.com

www.theluthierblog.com

Jo whoever he is.

Jo whoever he is.