Post by Martin on Apr 3, 2013 11:17:25 GMT

by Martin Robertson

_________________________________________________________________________________

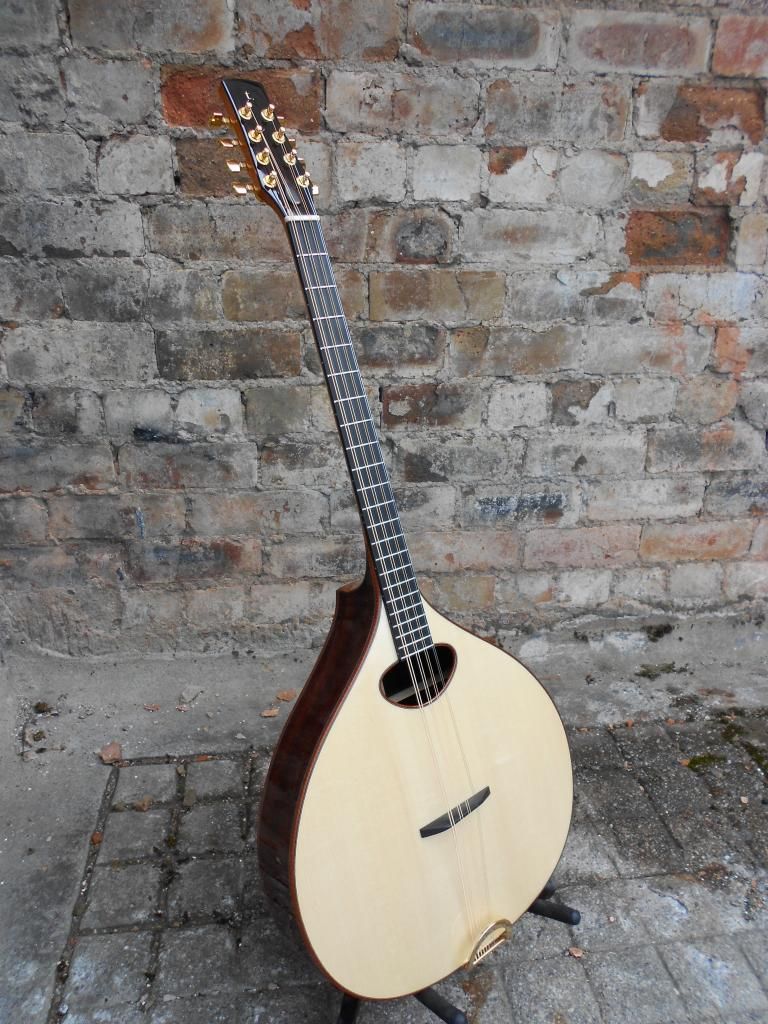

Rory Dowling (Taran Guitars) is a solo luthier based in Scotland, in the beautiful East Neuk of Fife not far from Edinburgh. He specialises in making flat top acoustic guitars and has a range of five guitars that he tailor builds for clients all over the UK and beyond. Rory also builds archtop bouzoukis, and is about to start building mandolins when he gets the time. He also offers a repair service with which he is kept busy, and his reputation stretches far and wide with clients often travelling hundreds of miles to get work done.

Martin: What made you want to start making acoustic guitars, and when did you start?

Rory: Well I started building instruments back in 2001/2002. I’m now 30, so that’s eleven years. Jings! In my second year at University after my cousin gave me the “Shady Grove” album by David Grisman and Jerry Garcia, I built an octave mandola; I wanted to play the Shady Grove tune so badly!

I studied furniture design and craftsmanship down in High Wycombe. It was a great degree that covered everything to do with the business of furniture and wood. As the mandola wasn’t a part of the course, I made it in the evenings in the open workshop that we had. The problem was that I enjoyed building the mandola more than I enjoyed building the furniture.

I ended up getting a first class BA (Hons) degree in the course but loved the idea of building instruments. I found instruments more tangible, which may sound mad because they are much more complicated, but it was their manageable size and endless intrigue that set the flame alight. That was in 2001/02, my first guitar came a few years after that and since then, I have been building guitars full-time.

Rory's first instrument - the octave mandola

Rory: The woodwork cross over from furniture to guitar building was more difficult than I had first anticipated. Initially, I knew how to work with wood as far as cutting and gluing went, as long as the chisel can shave the hair on your arm and your pencil isn’t a Mars bar then everything should work, but with guitars I started to understand that everything is so much more organic. Fundamentally, you have to learn how to work with the wood, to try to feel what it is doing and what it is capable of.

For example, when bending sides, you are bending with the grain so you really have to feel the wood relaxing on the bending iron and know when and where to put more pressure to create the correct curve in the side. Every piece of wood varies so much that even two rosewood sides for the same guitar will behave differently.

Therefore, for me it was about developing a tactile understanding of wood which enabled me to utilise any piece of wood in the best possible way.

Another key element was my understanding of the design process. I had built furniture and helped with house renovations in Sweden for a while; those guys know how to design! I found that this experience has really helped the development of my guitars. The design process is intrinsic to every part of my work whether it be the build process, the aesthetic of a particular instrument or working with a client to develop exactly what they want, it has made it all a lot more tangible.

Martin: What was your first guitar like, and did you know what you wanted to achieve at that stage?

Rory: Ah yes, ‘Lurch’ as it became known. Funny, my first instrument the octave mandola was okay, but Lurch was not! At the time we were playing a lot of gigs and I couldn’t afford a guitar so I set to and built one on a drawing board in a flat in Edinburgh.

There were just two of us on guitar, Pete played the harmonica and we both had bass pedals fixed to a cajon for the drum sections. We played a mix of dirty blues and folk with a lot of strong bass lines on top of melody with harmonic vocals. So sound wise I wanted a lot of bass in the guitar; Lurch had a little of everything! I went back to the drawing board and built another two guitars, one of which I sold, the other I played and now is on the wall.

Those two both had 'T.' on the headstock so yeah I knew what I wanted back then. I guess I’ve always wanted to make things with quality that stands out and at that time I was really hungry for a change in my career and, while very naive, building guitars just seemed right.

A couple of early guitars

Rory: Slowly at first! As I’m completely self taught in guitar building, the first few years were trial and error. The internet was helpful and I had the guitar building bible by Cumpiano, but the problem with the internet is that there are so many different opinions and the books covered everything about woodwork in a way that worked but that wasn’t really the way that I was used to working. So after a while I just dropped both and worked out the best way for me with the knowledge that I had.

After I set up my workshop in 2004 in Edinburgh, I was doing a lot of repairs but I was lucky because I always had an order to work on as well. The repair work in Edinburgh was great because I met a lot of players in town and around the central belt - great people like Kris Drever, Eamonn Coyne, Karine Polwart, Archie Fisher and Matheu Watson - and while I was interested in their repairs, I was more interested to hear about their views on music, sound and the instruments they wanted to play, what was good and what was bad.

You see I didn’t have a preconceived idea of what an instrument should be or what it should be capable of. The learning curve was very steep and with people around me like that, it made me push and push for better things; something I will continue to do.

I’m now based in Fife just outside Pittenweem in a workshop that I fitted out about a year and a half ago. It’s brilliant; the shop is beside our house so the commute can be arduous sometimes! The shop has a small machine area and large bench room where the wood burner is. I’ve got a set-up/repair room and finishing shop as well. I use the machine shop to process larger pieces of wood into guitar size bits. I try to reclaim as much wood as I can so this area just makes it more efficient to work in this way.

The East Neuk of Fife

The workshop before refitting

The workshop after refitting

When it comes to building the instruments I’m fairly traditional and do most things by hand on the bench. I had a finishing shop in the Edinburgh workshop but it was tiny so the new finishing shop is much more efficient. I was able to design and build it knowing exactly what I needed.

I used to get my instruments sprayed by David Wilson down in Haltwhistle. While he was very good, there were some areas that I wanted to develop, one of the main areas being the neck joint. In the past the neck was fixed before finishing but I needed the lacquer to be cleaner where the neck joins the body, so I moved to the traditional dovetail joint when I started spraying myself. On my guitars now the neck is fitted after finish which creates a super clear line at this point. I also wanted control over the thickness of the finish and future repairs that might have to be done should a client ding their guitar. It was a long and difficult process to get right but I feel so much better having control over the whole process now.

Martin: Is there anyone in particular who has influenced your building style?

Rory: A friend of mine was supporting Martin Simpson in Edinburgh about a year after I built Lurch. I, like many, was blown away by his sound. I noticed that his guitar was a little different so I had a chat with Martin at half time and managed to get a wee look at his guitar. The first thing I noticed was that the back was put on in a similar way to how I put on Lurch’s back. Knowing that I had done this differently to the standard way and also intrigued by the sound, I discovered that it was Stefan who had made it.

When building Lurch I would have never asked the piece of rosewood to bend in all directions. I thought surely an arch would vibrate much more freely than the standard dome whilst maintaining the structural integrity of the back; perhaps as Stefan had thought back in the beginning? I was later amazed to read that Stefan was also self taught and to see that we had done something in a similar way, gave me confidence to continue with my own personal journey.

For a while I asked David Wilson to lacquer my guitars, he also does Stefan’s. I was lucky enough to visit Stefan a few times when down picking up guitars. He gave his opinions on a couple of instruments. Stefan was a great help, he never told me what to do but definitely helped the way I think about guitars. So yes, I’m influenced by the Sobell philosophy but there are so many great builds here in the UK and in the States. I love Pete Beer’s work, a classical luthier in Somerset, as well as builders like “Grit” Laskin, Mike Greenfield and Kathy Wingert over the sea.

Martin: What is your philosophy behind a typical Taran guitar?

Rory: A typical Taran guitar? Well, I’ll start with the sound as it’s what it’s all about really. I look for a large dynamic in the range and good separation across the strings. By dynamic I mean the bass is full and strong, not 'woofy' in any way and the trebles are clear bell like and shimmeringly thick. I also need the mids to be even between everything with differing degrees of the above. I also need the guitars to have a lot of headroom so that they can be driven hard without breaking up. The separation is important to get right as if the range of each string over laps the next, then the guitar can sound jangly but if they’re too far apart, then you get a less versatile instrument. I’ve spent a lot of time working on this degree of separation in my Tirga Beag model. It’s my most popular guitar, I think the reason being because it’s so versatile in the styles it’s comfortable with.

I love it when you pick up a guitar and it makes a noise before you have even played a note. Response is massively important as is playability, the two go hand in hand.

I need the guitar to feel supple without flap or rattle. You can spend hours setting up a guitar which will help the playability but the fundamental behind a guitar that is great to play is that everything is working in the soundboard and that the strings’ energy is being used in the most efficient way possible. A responsive guitar will always play better. Naturally, string height and neck relief are very important and whilst I spend a lot of time getting these things spot on, they aren’t the only factors involved.

I put carbon fibre in my necks, a fairly new development that I started in the middle of 2012. This has made a massive difference. It makes the neck more rigid thus better at transferring energy but it doesn’t add mass so doesn’t suck tone away from the guitars’ soundboard. Another benefit is that the carbon combined with the plate tuning I do means there are no dead spots on the guitar. Every instrument has a resonate frequency, if this is the same as a note on the guitar, then when this note on the guitar is played, the note will go quiet or becomes a ‘wolf note’ as they are known. This is because the guitar is absorbing the frequency produced by the note. By tuning the soundboard and back in a certain way, I make sure that the top and back won’t create a resonate frequency that is bang on a note. Also by doing this I know that they are working together and not fighting one another. The guitar needs to sound balanced all the way up the neck compared to the open strings and it’s this tuning that aids this.

It has been said that I’m a little pedantic when it comes to my wood work! Well I represent that remark!

Yes I like things to be just so. Purfling mitres only meet perfectly at 45 degrees if you know what I mean. There are a lot of areas that I do because for me they work better and they look better. The arch backs help expand the range of the guitars and are also very comfortable for the player because the depth at the edge of the lower bout is a lot less than at the middle so you can play a bigger guitar and get a big sound from a guitar that feels smaller to hold.

Guitar interior

I build solid laminated linings in Fife Sycamore for more rigidity and I don’t get any nasty glue between the kerf cuts. The fluted rip stops, (the vertical bits on the inside sides) just because it makes me smile. But talking about rigidity! I’m making my first double sided Tirga Beag in Malaysian Blackwood and Scottish Sycamore. This again is to give the guitar more response, helped by this amazingly strong structure that does work that the top and back would otherwise have to do. I take no credit for this idea, a lot of builders do it but the fact that there always ways to make things sound better is brilliantly exciting.

Sycamore linings

One of the major factors when building a guitar is that the clients’ needs are taken care of. I spend a lot of time with my clients discussing tonal palettes and neck profiles, the ideal nut width and spring spacing, everything down to the colour on the inside of the case. It’s for them and while they come to me for my work, I want it to be theirs.

Martin: Your guitars and other instruments have a very sleek, minimalist look - is this something you deliberately set out to do, or is the design process evolving?

Rory: I definitely like the shape of the guitar and colour of the wood to do the talking. I spend a lot time thinking about my aesthetic, yes, they are quite minimalist, but this feel has taken time to get right. If a line of purfling is 0.1 of a mm too big relative to the rest of the guitar then I’ll sand off 0.1mm or if the black in a black white black purfling isn’t jet black then I won’t use it. I build all of my own bindings and purfling, I wouldn’t put a supplier through that! I suppose that wood is such a beautiful material that it should be treated with respect and not be over crowded with fuss.

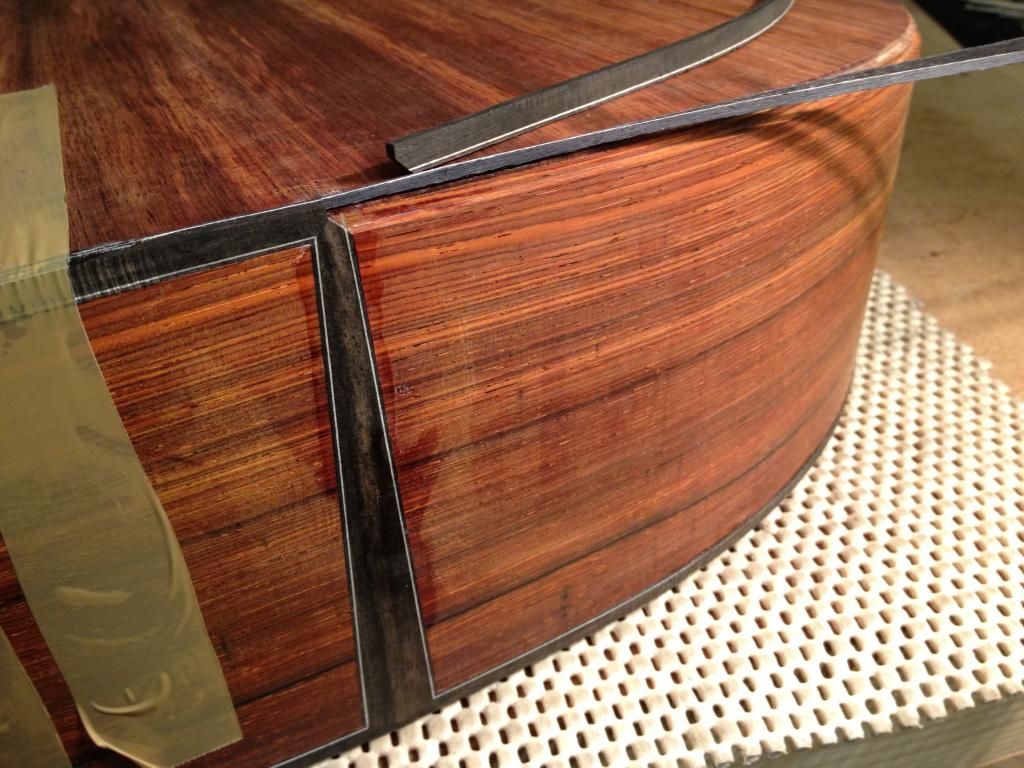

Is the design process evolving? Yes, all the time, I hope so anyway. I’m off down a different path at the moment, my rosettes have been a simple echo of the binding and purfling in the past and will continue to be for those who want that but I am gradually moving towards the ring rosette.

Cocobolo ring rosette

As a builder I’m always looking for new challenges whether it be sonically, ergonomically or aesthetically. One of the newest features that I do is the Laskin Bevel. Grit developed the idea some years ago and when I asked him if I could do it on my instruments he was very happy to let me.

‘Hey, just you remember to send me an image for my records, Rory!’ he said.

Martin: What different kinds of guitars do you enjoy building, and do you think the different models suit specific playing or music styles?

Rory: The model that I’ve been focusing on recently is my Tirga Beag. I’ve spoken a little about its versatility but it came about when Matheu Watson came to my workshop and brought the roof down with his playing, soon after he asked me to develop an instrument with him. He can play anything but predominately he plays Scottish Trad. This meant that we needed a guitar that would be comfortable with strumming for accompaniment and flat picking for his melody work. I’m onto the MKII Tirga Beag which does these things as well as finger style very well.

I’ve just strung up my first Dreadnought which is very exciting. I’ll report on that when I know more but the Dread model is something that I want to develop. In the past the Dreadnoughts that I’ve played have been disappointing, all woofy bass and thin trebles. I’m looking to apply my philosophy to the Dread size, to try and get that strong range with bags of headroom. The next one will be Mahogany Adirondack to give it that blue grass attack and volume but with that thick tone that I get from my soundboard design.

My other models like the Meilein Parlour and Taran Mhor offer a more intimate playing experience and are more suited to finger style, saying that, the Meilein in Sycamore is a great wee guitar for more bluesy playing as you get this crisp compressed tone, it’s surprisingly loud as well. I also build a large bodied 12-fret guitar called the Ulladale. It has a long scale of 660mm and is design for open tunings. It is great in C and holds those lower frequencies well.

Meilein Parlour

Ulladale Baritone

I had a guy in the other day who wants a guitar. He plays ragtime/blue grass and it was the Tirga Beag that he really liked. At the end of the day, I try to do something for most playing styles; they’re not just folk instruments.

Martin: What are your favourite tone woods to work with, how do you select them and how do they contribute to the sound you aim to produce?

Rory: When I pick up a piece of wood, I simply tap it with a knuckle and listen, it must ring or have life. It’s amazing, I bought a number of sets of Indian Rosewood, when I laid them out they all looked the same, they were cut from the same piece of lumber but when I went through them they all sounded different. My job is to put the right piece in the right guitar for the right person. That’s where the discussions come in; I have a very good idea of the sound that I and the client want before I select the parts for the guitar.

Rosewood features a lot. The sonic palette that you get from good Rosewood is amazing. I like Indian Rosewood, I love Cocobolo. I get a real power from Cocobolo and lots of depth and the overtones are equally as beautiful. I also like the African Blackwood guitars that I have made. While the fundamental is strong and the overtones not as prevalent as the Rosewoods, it creates a very strong tone that combined with my building style makes for (if I may say) an elegant sounding instrument.

Working with Cocobolo

In the soundboard department I love European Spruces, either Italian or Swiss. I find that they have an incredible amount of power and depth. These tops take time to develop but then if the guitar sounds good to start with, then it will only get better.

Neck material is so important but sadly it is getting harder to get top quality Brazilian Mahogany. I’ve been using reclaimed Brazilian for years now and hope that I can continue to. That is the Luthiers plight, finding woods that are responsibly sourced that are of good enough quality. On the flip side, you never know what new materials are just about the come up, like Malaysian Blackwood for example, I not sure if people were using that 10 years ago?

I’m also excited by the combinations of materials that I haven’t used yet, like Cedar and Walnut, Scottish Sycamore and Adirondack, Czech Spruce and Wenge. There are great woods, that aren’t Rosewoods, that do wonderful things to the sound and I’m looking forward to experimenting with them in my instruments.

Martin: You play guitar yourself - do you think this is important to being able to build an instrument more effectively?

Rory: I play but I’m not very good! No, it’s important to play but you don’t need to be a musical genius to build a guitar. Look at Bill Collings, he can hardly play a note, or so he says, but he understands what a great guitar should be. For me, the most important thing is to listen to what players want. I did a road trip a couple of years ago where I sent a guitar around just over thirty people from the Acoustic Forum (now Acoustic Soundboard) and other players a like. Everyone had the guitar for two weeks and then gave their feedback. Some even did videos and recordings of themselves playing, everyone was amazing and I am forever grateful to them all. The most valuable part for me was the chance to get a cross section of different players’ opinions, this way I could get an idea of what was good and, most importantly, what was bad, so that I knew what to improve on. I’m thinking about doing another one?

Martin: Just to finish up what is your year looking like and do you have anything exciting on the horizon?

Rory: This year is booked up which is a wonderful place to be. On the books I’ve got lots of guitars of various models, a bouzouki and violin. I’ve never made a violin before so I’m excited about that. I’m also going to try if I can find the time to build a mandolin as well. I’m interested in the A5 style mandolins, so it will be Adirondack and Scottish Sycamore with a hand rubbed sunburst finish.

I have also got a number of shows this year, one of which is in Edinburgh. This will be a great opportunity to touch base with people that I haven’t seen for a while and also to get to meet some new folk. The great thing about what I do is that I never know who is going to phone or visit the workshop to discuss a new guitar. At the end of the day I am constantly excited about continuing to develop, experiment and challenge my ideas about sound, design and instruments.

Taran Uke!!

Short video about Rory and Taran Guitars

Copyright Rory Dowling April 2013

Jo whoever he is.

Jo whoever he is.